Most discussions about the global weapons market rely on narrow statistics, usually arms exports or selected corporate revenues, that drastically understate its true scale.

When all quantifiable channels are combined, including domestic procurement, military services, advanced technology systems, ammunition production, upgrades, and long-term maintenance contracts, the real weapons-linked market rests between 700 and 900 billion USD annually.

This figure sits inside a global military spending structure of 2.718 trillion USD in 2024, the highest level ever recorded.

What makes the market difficult to measure is the way military procurement budgets, arms-industry revenues, cross-border deliveries, and dual-use technology become intertwined. A fighter jet bought in one year may generate ten years of follow-up contracts, software upgrades, engine overhauls, and weapons reloads.

A satellite system procured by a defense ministry might include civilian technology hidden inside other budget lines. And many countries do not publicly release full procurement data at all.

Why the Weapons Market Is Not the Same as Global Military Spending

World military expenditure rose by 9.4 per cent in real terms to $2718 billion in 2024, the highest global total ever recorded by SIPRI and the 10th year of consecutive increases.

New SIPRI data on #MilitarySpending out now ➡️ https://t.co/b3V9tMM6q7 pic.twitter.com/NdXK4nykhf

— SIPRI (@SIPRIorg) April 29, 2025

Global military spending reached 2.718 trillion USD in 2024, according to SIPRI, rising 9.4 percent in a single year, one of the steepest increases since the end of the Cold War. This massive pool of money often gives the false impression that the weapons market is equally large, but most of the spending goes somewhere else.

Salaries absorb a huge share, especially in countries with large standing armies; infrastructure and logistics eat another significant portion; pensions, operations, training, and fuel costs remove billions more.

Only a fraction of military budgets is spent on the procurement of new weapons or the modernization of existing systems. In many countries, that fraction ranges from 20 to 40 percent, and even withsubsetta subset, not everything becomes hardware.

Some budgets pay for cybersecurity, research labs, simulation systems, or maintenance of old platforms. This makes global military spending a misleading headline number; er it defines the ecosystem but not the true size of the weapons market.

The distinction matters because a country with a large budget may actually purchase relatively little hardware, while another with a modest budget may pour most of it into buying new equipment. This explains why military expenditure alone cannot show the true scale of the weapons economy.

Arms-Industry Revenue: The Best Window into the Real Market Size

View this post on Instagram

If there is one dataset that comes closest to capturing the weapons market, it is the collective revenue of arms-producing firms. SIPRI’s 2024 assessment shows that the Top 100 global defense companies generated 632 billion USD in arms-related revenue in 2023, a real-term increase over the previous year despite strained supply chains and rising input costs.

However, even this substantial figure underrepresents the true market. Several important layers remain uncounted:

- Many medium-sized national defense firms fall outside the Top 100 list, even though they produce key equipment such as short-range missile systems, armored vehicles, artillery, and communication platforms.

- Thousands of subcontractors, component manufacturers, ammunition producers, and specialized service providers generate billions of dollars annually, but are difficult to classify because they produce both civilian and military goods.

- A large portion of the Chinese defense-industrial base is opaque, and several Chinese companies do not report clear distinctions between civilian and military revenue streams.

- The fastest-growing sectors, cyber operations, space-based military platforms, satellite imaging, and artificial intelligence, are heavily embedded in the tech industry rather than traditional arms firms.

When these elements are added together, analysts assess that the realistic industrial value of the weapons market falls between 700 and 900+ billion USD annually. This estimate forms the backbone of the modern global weapons economy.

The Geography of Arms Production: Who Actually Builds the World’s Weapons

Although dozens of countries operate defense industries, global production is heavily concentrated. The United States alone accounts for an extraordinary share of global procurement and export capacity.

Europe, especially France, Germany, Italy, and the UK, maintains broad, technologically sophisticated production lines. Russia remains a major actor, though its export capacity has shrunk sharply due to sanctions and the demands of its ongoing war. China has built one of the world’s largest domestic defense industries, but exports far less than its production capacity might suggest.

Regional players such as South Korea, Israel, Türkiye, and Norway have undergone rapid expansion, not just producing weapons but also innovating in drones, missile systems, and naval technologies. These countries increasingly fill the market gaps left by Russia’s weakened position as an exporter.

The industrial geography shapes global politics: nations with strong arms industries influence their alliances, their conflicts, and their trade relations. The global weapons market, therefore, is not just an economic structure; it is a map of geopolitical leverage.

International Arms Trade: The Most Visible but Smallest Slice of the Market

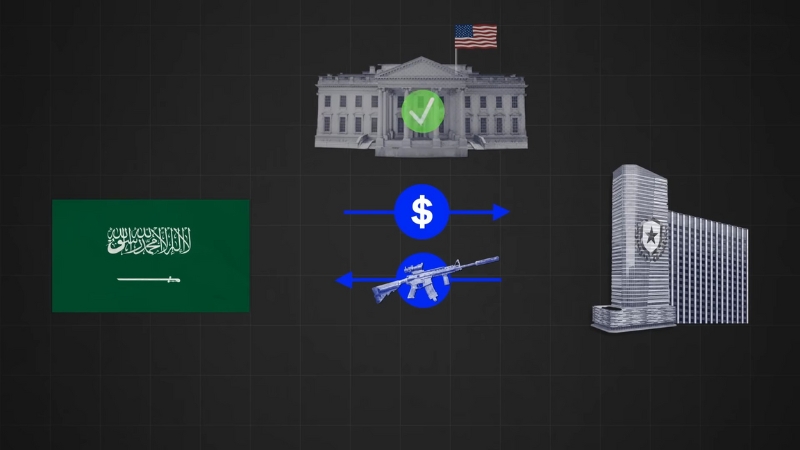

International arms transfers represent only a portion of the weapons market, but they matter disproportionately because they alter the military balance between states. SIPRI’s latest fact sheet shows that the overall volume of major arms transfers remained essentially flat when comparing 2015–19 with 2020–24, declining by only 0.6 percent.

Yet beneath this stability lies major regional change.

Europe has seen an unprecedented surge in imports. Driven by the Ukraine war, European states increased their weapons imports by 155 percent over the period.

Meanwhile, the Middle East remains a consistent importer of advanced air and missile defense systems. Asia and Oceania continue to purchase large quantities of naval and missile assets due to rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific.

The financial value of these cross-border deals is estimated at 100 to 120 billion USD annually, though the amount varies by year. Some deals span long time horizons, meaning a single contract signed today may be delivered over a decade.

Major Arms Exporters, 2020–2024

The visibility of these export flows often leads observers to underestimate the scale of the weapons market. Cross-border transfers are essential for regional security, but they represent only a fraction of the money that flows through the broader defense economy.

Domestic Procurement: The Invisible Majority of Global Weapons Spending

Most weapons never leave the country in which they are built. Countries such as the United States, China, India, and Russia operate large domestic procurement systems that rarely appear in international arms trade statistics.

Domestic procurement includes fighter jets, tanks, artillery, missile systems, naval ships, helicopters, ammunition, communications systems, satellites, cyber-defense infrastructure, and maintenance contracts.

It also covers a vast volume of personal equipment at the soldier level, from night-vision devices and individual radios to body armor. In that category, modern plate carriers and ballistic vests, including widely used solutions such as shellback plate carriers and comparable systems, represent a steady, recurring stream of spending that rarely shows up in big-ticket export headlines but adds up across entire armies.

Domestic procurement includes fighter jets, tanks, artillery, missile systems, naval ships, helicopters, ammunition, communications systems, satellites, cyber-defense infrastructure, and maintenance contracts.

These domestic purchases often exceed the value of a country’s entire arms exports. For example, the U.S. procures billions of dollars in aircraft, missile defense systems, and naval technologies internally every year, none of which appear in the global trade figures.

This internal demand is one of the reasons the weapons market is significantly larger than the export market. Domestic spending drives industry growth, sustains research and development, and shapes long-term technological leadership.

Emerging Technologies: Why the Market Is Growing Even If Unit Volumes Are Flat

One of the most important drivers of market expansion is technological complexity. A modern fighter jet or integrated air-defense system is far more expensive than its counterpart 20 years ago, not because of inflation, but because of embedded electronics, software, and network integration.

Even when the number of weapons produced stays flat, the value of contracts rises sharply. Military platforms today include sophisticated surveillance technology, encrypted communication systems, advanced sensors, multi-domain integration, and cyber-hardened software. Some systems rely on AI-enabled targeting or autonomous navigation, which adds further cost.

This modernization trend is visible in Europe, the Middle East, and the Asia-Pacific. Countries are not only buying more weapons, but they are also buying systems that require constant upgrading, maintenance, and digital modernization. This alone pushes the weapons market toward the higher end of the 700–900 billion USD range.

The Hidden Layers: Classified Budgets, Dual-Use Sectors, and Illicit Flows

Not all defense spending is transparent. Classified programs account for billions of dollars annually across most major powers.

These include intelligence procurement, covert cyber programs, black-budget weapons testing, and clandestine operations. They are reflected in global spending totals but not in procurement or trade figures.

Dual-use technology adds another layer of complexity. Many companies supplying AI chips, satellite systems, multispectral imaging sensors, secure communications, and cyber-defense tools do not categorize their revenue as military, even when defense ministries are major clients. This complicates any attempt to measure the true arms-linked economy.

The illicit weapons market contributes a much smaller monetary volume but has enormous geopolitical consequences. Global Financial Integrity estimates that 1.7–3.5 billion USD of illicit small arms circulate each year, while European studies suggest 125–236 million euros of illegal firearms trade on the continent.

These figures do not significantly alter the total weapons market size but shape instability, insurgency, and organized crime worldwide.

Conflicts and Regional Tensions: How Wars Reshape Demand

Modern conflicts exert strong gravitational effects on the weapons market. The Ukraine war has transformed Ukraine into the world’s largest importer of major weapons from 2020–24, recording a staggering 9,627 percent increase in arms imports compared to 2015–19.

European states, responding to regional insecurity, have launched some of the most aggressive rearmament programs in decades, dramatically increasing demand for artillery, air-defense systems, drones, and ammunition.

The Middle East continues its decades-long procurement of advanced air and missile defenses, while heightened regional tensions have caused spikes in spending in Israel and several Gulf states.

In the Indo-Pacific, Japan, Australia, India, and South Korea invest heavily in naval systems, hypersonic technology, and autonomous platforms in response to China’s rising military power.

These regional pressures ensure that the global weapons market is not just stable, it is intensifying in both value and strategic significance.

Bottom-Line

Component

Estimated Annual Size

Source

Global Military Spending

2.718 trillion USD

SIPRI

True Global Weapons Market (Industrial + Procurement + Services)

700–900+ billion USD

Derived from 632 billion Top-100 revenue + uncounted firms and dual-use sectors

International Arms Trade

100–120 billion USD

Multiple analyses + SIPRI transfers

Illicit Weapons Flows

2–4+ billion USD

GFI & Europol estimates

The real weapons-market figure cannot be extracted from exports alone or from military budgets alone. Instead, it must be reconstructed from the industrial base, the procurement lines, the services ecosystem, the modernization cycle, and the classified components hidden within national defense architectures.

The most realistic, evidence-based conclusion is therefore clear:

The global weapons market, meaning the total value of weapons, munitions, upgrades, and military services purchased annually, stands between 700 and 900 billion USD and is rising.

It is one of the most powerful economic and geopolitical forces in the world today.

Dave Mustaine is a business writer and startup analyst at Sharkalytics.com. His articles break down what happens after the cameras stop rolling, highlighting both big wins and behind-the-scenes challenges.

With a background in entrepreneurship and data analytics, Dave brings a sharp, practical lens to startup success and failure. When he’s not writing, he mentors founders and speaks at entrepreneur events.